People are able to connect more easily to things that are concrete, especially unfamiliar things. If you want to explain something to a large group of people, the easiest language for them to understand is concrete language. That’s one of the reasons Aesop’s Fables are so enduring (the other reason is that they are stories, but we’ll get to that later). Aesop’s Fables take an abstract concept like “slow and steady wins the race” and put it into concrete terms. An oil painting is concrete, expressionist mood is not.

Related to the idea of instructional scaffolding in education, concreteness helps people build on their existing knowledge (schemas) to advance into abstract ideas. Abstraction is the luxury and the curse of experts. How many of us would care to read a peer-reviewed journal article about differentiating synchronic and diachronic analysis in semiotics? A professional chef wants to discuss the philosophy of haute cuisine, not swap recipes. The notion that abstraction is the luxury of experts might help to explain what happens when museum curators are in charge of writing for the general public.

Ask yourself why to avoid the curse of the expert:

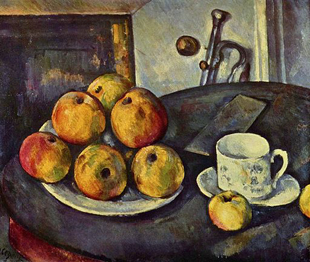

Expert: Paul Cezanne was influential in the development of the Cubist movement.

Why?

Expert: Objects in his paintings shift in and out of perspective.

Why?

Use this: He wasn’t interested in how things looked, instead he tried to record the act of looking.

Concrete details help make lasting memories. Memory is like Velcro. Lots of little loops on the brain side of the tab connect with hooks created by experiences on the other side. Concrete experiences create lots of hooks to connect with the loops, and as a result stick one tab more firmly to the other. Try this exercise from Made to Stick.[1] Answer the questions below by taking some time to think about each one.

What is the capital of Kansas?

What is the first line of “Hey Jude”?

What does the Mona Lisa look like?

Remember the house where you spend most of your childhood.

What is the definition of truth?

What does a watermelon taste like?

As you moved through the questions, you probably noticed that it feels different to remember different kinds of things, depending on how concrete the answer is, whether you ever knew the answer in the first place, and how many hooks you already have to in place to help you remember. We all use different parts of our brains to remember different things.

Remembering the house where you spent most of your childhood was probably pretty easy. All the different experiences you had in the house created lots of sticky Velcro hooks. The definition of truth was probably a lot harder – it’s an abstract concept. The Heath Brothers who wrote Made to Stick recommend that if you don’t know the Hey Jude song you trade their book for a Beatles album. They think you’ll be happier.

- Heath, Made to Stick, 110. ↵